EACH of these essays/entries is intended to stand alone, so there is a certain degree of duplication in them as it is unlikely they will be read in sequence or even that all will be read by a visitor to these pages. This is intentional: someone reading an essay/entry must not be puzzled by some allusion she or he might not understand because they have not read the other essays/entries.

It may be said flatly that the famous Hemingway style is neither so clear nor so forceful in most passages of ‘Death in the Afternoon’ as it is in his novels and short stories. In this book Mr Hemingway is guilty of the grievous sin of writing sentences which have to be read two or three times before the meaning is clear. He enters, indeed, into a stylistic phase which corresponds, for his method, to the later stages of Henry James.

In Our Time and its predecessors Three Stories And Ten Poems and in our time [sic — the lower case initials were intentionally] distinguished themselves by ‘being different’. Some might like and enjoy the style in which they are written, others not so much. I don’t.

Almost one hundred years later, they strike me as little more than what they were: the work of a keen, still quite immature, young man with a high opinion of himself and his abilities and not shy about sharing his enthusiasm. In the New York City Sun, Herbert Seligman paid the collection a rather left-handed compliment and wrote

The flat even banal declarations in the paragraphs alternating with Mr Hemingway’s longer sketches are a criticism of the conventional dishonesty of literature. Here is neither literary inflation nor elevation, but a passionately bare telling of what happened.A British reviewer, in the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, is rather less hi-falutin’ and strikes a good and fair balance. He (or she) noted about the collection

There is vigour, too, and a personal quality of observation in his stories and vignettes; but nothing that one wishes particularly to remember seems to us to emerge from them. The general atmosphere might be described as one of American adolescence — a hard, sterile, restlessness of mood conveyed in a hard, staccato sometimes brutal prose. Mr Hemingway uses his method very skilfully; we feel he is both sincere and successful in carrying out his purpose, but his purpose seems to us narrow and unfruitful — withered at the root.Pertinently he (or she) adds

[Hemingway] is a natural writer who has not yet found an environment worthy of him.Most of the stories show promise and up to a point some work, though relying heavily, it has to be said, on being ‘different’ to then contemporary work. To my mind Soldier’s Home, Cat In The Rain, The Doctor And The Doctor’s Wife and The Battler pass muster. Several others — The Three-Day Blow, The End Of Something and Out Of Season — almost get there, but in each something is be missing.

Other stories just make up weight and do not connect. One, A Very Short Story, shows Hemingway at his adolescent worst and one wonders how it even made it into the collection.

Perhaps he was, as a still inexperienced writer, not aware of how pointless and dreadful it was, but his Scribner’s editor Max Perkins would and should have done, should have told him and dropped it (as he insisted Up In Michigan should be dropped).

The collection’s final story, the two-part Big Two-Hearted River is a puzzle: grand claims were and still are made that it is a psychological examination of a young man returning from war rather disturbed by what he has gone through. Hemingway later claimed that was what the story ‘was about’, and once he had made that claim, it became the orthodox interpretation, repeated by students to this day, mainly because that is what they have been taught in class.

Notably, no readers picked up on that ‘meaning’ until Hemingway made his claim: the text does not support that it at all. Frankly, the story is little more than a rather long-winded account of a fishing trip, of little interest to anyone except those who enjoy fishing (and if you enjoy going fishing, perhaps it is not quite so long-winded).

As for the ‘meaning’, various and often contradictory interpretations of other Hemingway stories over the years should alert us that, as I spell out earlier, that something akin to along the Rorschach effect is at play: we often see what we want to see (and that is certainly true in life generally).

One could go a little further: if Hemingway is right about what the story ‘means’ — or better what he intended it to ‘mean’ — Big Two-Hearted River should be chalked up as an artistic failure. He might have assumed that, according to his rather threadbare ‘iceberg theory’, if he was writing ‘truly’ enough, what he ‘knew’ would somehow come to be known by the reader. Well, does it? I don’t think so, though you might.

But how can you be sure that the subsequent ‘explanation’ — initially from Hemingway, later in class — didn’t influence you? Can you recall what you first thought?

As I point out above, these matters are personal. My scepticism is no more — though no less — valid than whichever interpretation you choose to champion. Thus, for you, perhaps, the story is not ‘an artistic failure’. Each to his own.

In 1926, the stories Hemingway published in In Our Time were sufficiently unusual to raise the hopes of Scribner’s and Max Perkins that his first novel would cause waves. And it did, although it strictly it was no his ‘first’ novel, but that has been covered elsewhere. The Sun Also Rises certainly established Hemingway as the writer to keep an eye on.

From all sides the novel received often rapturous praise, but in hindsight that praise tells us as much about the publishing industry, its symbiotic relationship with ‘the critics’ and that eternal desire for ‘something new’ as about Hemingway. Eighty years on it, too, can be viewed more dispassionately.

Grand claims are still made for the novel and its significance, but it strikes me as essentially a sour anti-romantic potboiler rather than a profound work examining a group of young people ‘in despair’. In his review for the magazine New Masses, John Dos Passos was harsh and wrote

Instead of being the epic of the sun also rising on a lost generation, [The Sun Also Rises is] strikes me as a cock and bull story about a lot of summer tourists getting drunk and making fools of themselves at a picturesque Iberian folk-festival. It’s heartbreaking. If the generation is going to lose itself, for God’s sake let it show more fight . . . When a superbly written description of the fiesta of San Fermin in Pamplona . . . reminds you of a travel book . . . it’s time to hold an inquest.Dos Passos was almost certainly writing to a brief, the avowedly left-wing New Masses wanting to hear nothing positive about Hemingway’s gaggle of middle-class ex-pats — and Dos Passos did later apologise to Hemingway for his review.

But he does get closer to the truth than many an academic Hemingway stalwart might care to acknowledge — Carlos Baker and Philip Young made some extremely silly claims twenty years later about symbolism and alleged significance in the novel.

In Ernest Hemingway: A Reconsideration first published in 1952 and revised in 1966) Phillip Young writes

Despite quite a lot of fun The Sun Also Rises is . . . Hemingway’s Waste Land and Jake is Hemingway’s Fisher King. This may be just coincidence, though the novelist had read the poem, but once again here is the protagonist gone impotent, and his land gone sterile. Eliot’s London is Hemingway’s Paris, where spiritual life in general, and Jake’s sexual life in particular, are alike impoverished. Prayer breaks down and fails, a knowledge of traditional distinctions between good and evil is largely lost, copulation is morally neutral and, cut off from the past chiefly by the spiritual disaster of the war, life has become almost meaningless.This claim was soon dismissed by W.J. Stuckey in short order:

A Waste Land that is fun doesn’t make a great deal of sense, or, at any rate, makes a sense very different from that of Eliot’s poem and would therefore demand a different sort of reading.Stuckey again makes the point that

. . . what The Sun Also Rises requires — what critical responsibility requires — is that Hemingway’s novel be examined in the light of its own working, not by the alien light of another very different sensibility.There was and still is little hope of that, though.

Like other early work by Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises is also markedly a curate’s egg. Some of it entertains, much of it is padding, and there are some excessively flat and banal passages, although as I concede above, each to his own — my ‘flat and banal’ might well be your ‘Hemingway’s unique style’.

The work might, arguably, have been cut and tightened and become a rather better novell’ but at the time a keen young Ernest Hemingway knew he had to produce a novel-length work to get his career off the ground — a novella would not do.

A year later came Men Without Women, his second collection of short stories. It, too, sold well and was mainly praised by the critics, but it did attract the stinging rebuke from Virginia Woolf that although

Mr Hemingway . . . is courageous; he is candid; he is highly skilled; he plants words precisely where he wishes; he has moments of bare and nervous dutyshe adds, in retrospect perspicaciously, that

he is modern in manner but not in vision; he is self-consciously virile; his talent has contracted rather than expanded; compared with his novel, his stories are a little dry and sterile.Quite early on there were doubts that Hemingway was really the ‘modernist writer’ he was touted as. Men Without Women also demonstrated why he was, as I suggest, a middling writer and not ‘great’.

For example, The Killers, his tale about two hitmen who turn up in a diner waiting to kill a Swedish boxer who had double-crossed someone, is anthologised, lauded and analysed, but it doesn’t fully convince. Half-shut your eyes and ignore — as contemporary reviewers, of course, could not — that it was by ‘that exciting new writer Ernest Hemingway’, and it reveals itself more as a pale attempt to emulate the hard-boiled style of Dashiell Hammett.

It does not strike you as a piece of the ‘great literature’ Hemingway was now priding himself on producing. However, that nowadays the story receives more academic attention than Hammett and is certainly filed in a different box has little to do with its literary quality than because it is by ‘Ernest Hemingway’.

Having thus crossed that threshold, it gains marks for ‘reflecting’ the stoicism of the Hemingway ‘code hero’. That is all fine and dandy, but at a more technical level it does demonstrate artistic flaws, not least in how Hemingway handles, or rather mishandles, the passage of time.

There are curious niggling lacunae in the story which a more gifted writer might have dealt with. We are also assured that the story deals with ‘the coming of age’ of — though unnamed in the story — Nick Adams. The lad is apparently so unnerved by the two hitmen and especially by the Swedish boxer’s stoic resignation to his fate that he feels obliged to leave town.

Why? Perhaps I am missing something, but Nick’s reaction is inexplicable and one does wonder what happened to his own stoicism. Yet ‘Nick leaving town’ is touted as ‘significant’.

The theme of stoicism in the ‘code hero’ turns up in The Undefeated, a tale about an ageing bullfighter on the skids who finally meets defeat in the ring and eventual death, but who remains undefeated in spirit.

It is a touching story, but it, too, is flawed: Hemingway gives too much space describing the bullfight itself, to the point where his enthusiastic, in context excessively detailed, blow-by-blow account swamps the story; yet the story is the ageing man’s fate, not his last bullfight.

A better and more skilful writer — and a more aware artist — might well have realised the fact and, with his readers in mind, curbed his enthusiasm.

Another highly praised story in the second collection also suffers from artistic flaws. Hills Like White Elephants deals with a young man and his partner — whether wife or lover we are not told — who are sitting on a station platform waiting for a train. Notably, the young man is — or is generally assumed to be — trying to persuade the young woman to have an abortion.

This was shocking stuff for 1927 fiction to deal with and was taken at the time as another sign that Hemingway ‘was modern’. Yet again Hemingway fails to convey the passing of time convincingly. We hear the conversation between the two characters about a potential abortion, yet the dialogue as reproduced by Hemingway would have been concluded in a few minutes.

Thus the couple either also talk of other matters — not recorded — or they sit in silence; and given the testy atmosphere, that silence would have been uncomfortable, and thus arguably of dramatic interest.

Either way, I suggest, it would have been pertinent and Hemingway might have incorporated that passing of time into his narrative.

Quite how the author might have dealt with it is not the reader’s concern: it is for the author to tackle in whatever way she or he feels fit. All we, the reader, know is that there is ‘something missing’.

Hemingway also exhibits a quirk in this story which often occurs in his writing: when he seems at a loss as to what next to do with a character, he has them ‘have a drink’. So while waiting for their train, the man and the woman each has two glasses of beer and, in addition while passing through the station buffet, the man treats himself to anisette.

This, too, is oddly out-of-kilter: the pair were waiting long enough to have two glasses of beer each and these would not necessarily be finished off in a matter of minutes (and the train has still not arrived by the end of the story). So time passes which is not accounted for, and again we are left high and dry as to elements in the story which trouble by their absence.

Hemingway might have believed that his ‘iceberg theory’ was here in play and that by writing ‘truly’, it would all somehow be conveyed to the reader. Well, here and in other stories, it isn’t: there are odd lacunae which ensure the story overall doesn’t work, the story is too syncopated and so it, too, doesn’t quite convince.

When I first came across Hemingway’s work many years ago, I would have assumed the writer knew what he was doing and that if I did not quite ‘get it’, if I was somehow troubled by some aspect of a story, I was necessarily to blame. After all, Hemingway was, I was assured, a ‘great’ writer. I am no longer as credulous.

As with the first collection, some stories do work: Canary For One, A Simple Enquiry and — a rather odd but effective story — A Pursuit Race. Several are hit and miss, but others, A Banal Story and especially Today Is Friday simply do not work at all. The point is that these stories are, according to Matthew Bruccoli before 1929, part of Hemingway’s ‘best’ work.

You might argue that not everything can or must be pitch-perfect, yet an almost consistent pitch-perfection is what we are accustomed to from those we regard as ‘great artists’ working in many other fields; and it is with such men and women that Hemingway champions ask us to rank their hero.

As part of Hemingway’s pre-1929 ‘best work’ Bruccoli also included his second novel, A Farewell To Arms, and it, too, can stand proud with similar fiction of its kind; yet it would be more appropriate to class it as an ‘adventure story’ than as ‘great literature’.

The derring-do of its main protagonist — as usual Hemingway more or less in fictional form — is entertaining enough and rattles along well. The novel’s overwhelming flaw is its ‘love story’. It is quite awful and, as one critic said of its even less convincing counterpart in For Whom The Bell Tolls, it is ‘adolescent fantasy’. Hemingway was hopeless at conveying love and romance.

In The Sun Also Rises, he more or less managed to convince the reader that Jake Barnes and Brett Ashley were sweet on each other, but theirs was no profound love. In his subsequent three novels Hemingway demonstrated that his slight success with Barnes and Ashley was a fluke. In none does he come anywhere close to presenting a convincing, believable romantic heroine and halfway decent love story.

Catherine Barkley almost doesn’t even make it into two dimensions, let alone three, and she is so drippy that you want to strangle her. Furthermore, although Frederic Henry’s and Catherine’s love affair begins in and evolves out of the war they are part of, the two themes — love and war — lose each other entirely. They become wholly independent and by the end of the novel the war is simply forgotten.

So what is the novel’s theme? What is it about? War in its many manifestations? Or a love affair, tragic in that ‘the girl’ dies giving birth? Either way the novel sells the reader short: the war element is finally left hanging, and the love element is too thin to sustain the novel, despite the tragic ending of the heroine’s death in childbirth.

The lack of cohesion in the two themes did not just trouble Max Perkins, but the celebrated novelist Owen Wister. Perkins asked him to supply and endorsement for Hemingway’s then latest novel. In the publicity blurb used by Scribner’s he wrote

In Mr Ernest Hemingway’s new novel a Farewell to Arms landscapes, persons and events are brought to such vividness as to make the reader become a participating witness. This astonishing book is in places so poignant and moving as to touch the limit that human nature can stand when love and parting are the point . . . And he, like Defoe, is lucky to be writing in an age that will not stop its ears at the unmuted resonance of a masculine voice.But as biographer Michael Reynolds records

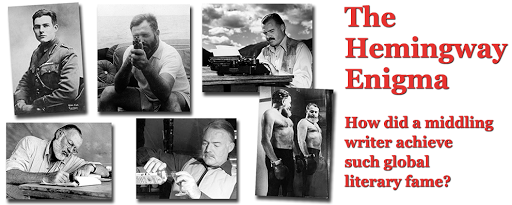

In a separate statement to Perkins, Wister voiced his concerns about Hemingway’s use of the first-person narrator and the novel’s conclusion, suggesting that the nurse’s death be softened and that the ending bring together to two themes of love and war. Perkins agrees completely. The book’s flaw, he tells Wister, is that the war story and the love do not combine.As Hemingway had demonstrably lost control of his material, on the basis of these two novels and two collections of short stories it would not be unfair to describe him as a middling writer. But mark: these four works were, in Bruccoli’s view, ‘his best’. What might is ‘not quite his best’ look like?

Max Perkins was reputedly not overly pleased when Hemingway, flushed with the critical and commercial success of A Farewell To Arms and convinced that as a writer he could do no wrong, announced that his next book would be a guide to bullfighting.

But the sales so far had pitched Hemingway into a strong position, and Perkins went along with the plan. When Death In The Afternoon was published, Hemingway had just turned 33, but he now saw himself as an authority on writing. Death In The Afternoon was thus presented not just as a guide for English speakers to all aspects of bullfighting but as his guide to what constituted ‘good writing’.

The link between the two themes was his central conceit that in many ways bullfighting was very much like writing: both the matador and the writing ‘took risks’.

However, the book did not sell well and by some accounts barely broke even. It’s lack of commercial success might have little bearing on whether or not Hemingway was a great writer, but as several critics pointed out the contents of his latest book did: for a ‘great writer’ Hemingway did not write very well in Death In The Afternoon. The reviewer of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin noted that

In his enthusiasm for the art of tauromachy, Mr Hemingway has departed, sadly, in places from his usually clear and forceful style. His earnestness in trying to put over his idea apparently has caused him to neglect pruning. The result is a surprising loss of conciseness, and occasionally a deplorably cluttered syntax.Those who might insist that Hemingway’s reputation as ‘a great writer’ rests on his fiction rather than his non-fiction might care to note that was not what the man himself believed.

By the early 1930s he certainly did regard himself as ‘a man of letters’, and that conviction was not just demonstrated in his confident pronunciations de haut on what ‘good writing’ was, but what he told friends and acquaintances in letters. The literary establishment was less convinced. As R L Duffus wrote in the New York Times

It may be said flatly that the famous Hemingway style is neither so clear nor so forceful in most passages of Death in the Afternoon as it is in his novels and short stories. In this book Mr Hemingway is guilty of the grievous sin of writing sentences which have to be read two or three times before the meaning is clear. He enters, indeed, into a stylistic phase which corresponds, for his method, to the later stages of Henry James.

What was going on? Duffus criticism is especially pertinent given that as a former journalist Hemingway would have been aware of the imperative for clarity. It is tempting to ask whether he even re-read his work.

On the face of it that is very unlikely as he will have been asked by Scribner’s to correct galley proofs, but you do wonder why he didn’t seem to have realised his prose was confusing.

Next came more fiction, a third collection of short stories. Its sales were more gratifying for Scribner’s and Max Perkins than those of Death In The Afternoon, but they were not as great as those of his previous two collections.

Some critics were also a little underwhelmed by the stories and felt that success and the good life had rather blunted Hemingway’s sensibilities. Ironically, as he described recorded in his story The Snows Of Kilimanjaro, that was also his concern. In the New York Times, John Chamberlain noted that

. . . [Hemingway] has evidently reached a point in writing where the sterile, the hollow, the desiccated emotions of the post-war generation cannot make him feel disgusted; he is simply weary of contemplation. He feels sorry for himself, but he has lost something of the old urgency which impelled him to tell the world about it in good prose.Writing in Nation, William Troy was blunter:

It is among Mr Hemingway’s admirers that the suspicion is being most strongly created that the champion is losing, if he has not already lost, his hold.Even Malcolm Cowley, a lifelong Hemingway champion, was disappointed. Reviewing the 1938 publication by Scribner’s of Hemingway’s play The Fifth Column and The First Forty-Nine Stories, he described those in Winner Take Nothing as

a rather meagre collection.In my view, this third collection contained more misses than hits, and even the more successful stories showed signs of laxity.

For example, as the young Turk in Paris under the tutelage of Ezra Pound, Hemingway had made great deal — following Pound’s guidance — of eschewing adjectives and adverbs and ostentatiously establishing a new, modern style.

Yet just eight year later, by 1934 when Winner Take Nothing appeared, his scorn for such linguistic fripperies had vanished. In The Capital Of The World, we get a young woman ‘laughingly’ refusing, priests being ‘hurriedly’ conscious and one waiter walking ‘swingingly’ away.

There is nothing at all ‘wrong’ with these constructions — after all each to his own as the liberal in me keeps preaching — but the style does smack more of work produced in the first semester of a creative writing course than that of ‘one of America’s greatest writers’.

Even The Capital Of The World, one of the collections better stories, has a notable flaw — it is oddly amorphous: what is it about? The story’s first half seems to reflect the title in that we are presented with a cross-section of guests at a small Madrid lodging house as one might find at random in a capital city.

The lives of several are described, but then the story goes off at a tangent. We read about a young lad, a waiter with ambitions to become a matador, who bleeds to death when a piece of juvenile tomfoolery goes wrong. By then the story’s other protagonists are forgotten, disappear, abandoned. Such criticism might be dismissed except that the story’s title, The Capital Of The World, seems irrelevant to the tragic outcome.

Because Hemingway told us, we know that his usual way of composing a story was simply to set off without a plan and see where he might end up. Every writer can, of course, proceed as they wish: we are only interested in what they produce.

But The Capital Of The World has a distinctly odd shape. Would not a ‘great writer’ revisit a work once the first draft is concluded, reappraise and consider it, and, applying her or his artistry, revise it to create a coherent and self-contained whole?

There is, after all, no deadline and the writer can take just as long as he or she likes to achieve whatever effect he or she wants. What effect was Hemingway trying to achieve in that story?

Despite Hemingway’s claims that he spent hours working ‘hard’ searching for the right word and revising his work, one is often left with the distinct impression that he cut corners. This is apparent in another of that third collection’s more celebrated stories, A Clean, Well-Lighted Place, notably in its ‘insoluble problem’.

I have dealt with that and the various ‘solutions’ to that problem elsewhere, but one academic who examined the story’s original draft concluded that it was written in haste, and the few revisions made were done on the same or the following day, but the confusion — the ‘insoluble problem’ — was left unresolved. Is this the practice of ‘a great writer’?

On a sidenote, the standard claim that the theme of this relatively slight story is ‘order and light against the chaos of darkness’ or some such line tells us more about the compulsive search for ‘literary meaning’ among academics and critics than anything else.

Rather than invoke such foggy metaphysics, a rather simpler evaluation might be that of the two waiters in a café waiting for their last customer, an elderly man who had recently tried to hang himself, to leave, the older waiter can empathise with the customer’s loneliness whereas the younger, brasher waiter cannot.

Even less successful than Death In The Afternoon was Green Hills Of Africa, Hemingway’s account of his East African safari of which Edmund Wilson noted that

He delivers a self-confident lecture on the high possibilities of prose writing, with the implication that he himself, Hemingway, has realized or hopes to realize these possibilities; and then writes what are certainly, from the point of view of prose, the very worst pages of his life.Wilson, who had also been an early champion of Hemingway a decade then adds with astonishment that

There is one passage which is hardly even intelligible — the most serious possible fault for a writer who is always insisting on the supreme importance of lucidity.Once again: what was going on? Nor did the great writer redeem himself with his next work, the novel To Have And Have Not. The public liked it and bought it, but the critics were unimpressed and the ‘great’ writer’s career was flagging badly.

The novel was cobbled together from two previously published short stories and a newly written novella. Hemingway wrote it in response and against his better judgment to demands from the left to become ‘more socially-engaged’. He was also keen to get off to Spain to cover the civil war that had broken out and his heart simply wasn’t in it.

His career was unexpectedly revived with For Whom The Bell Tolls, but that novel, too, is like most of Hemingway’s work, very much a curate’s egg. It was also a halfway decent adventure story marred by a ‘romance’ which would even have been risible in a bad chick-lit novel.

Hemingway who had been noted for his dialogue quite simply forgot how to write it in For Whom The Bell Tolls. Reviewing his earlier novel The Sun Also Rises, the New York Tribune had noted that

The dialogue is brilliant. If there is better dialogue being written today I do not know where to find it. It is alive with the rhythms and idioms, the pauses and suspensions and innuendos and shorthands, of living speech. It is in the dialogue almost entirely Mr Hemingway tells his story and makes the people live and act.Equally enthusiastic was Britain’s Nation & Athenaeum in its review of that novel:

Mr Hemingway is a writer of quite unusual talent . . . His dialogue is by turns extraordinarily natural and brilliant, and impossibly melodramatic . . .But already by 1937 when he published To Have And Have Not, Hemingway had somehow taken such a wrong turn that in the New York Times J Donald Adams finds that the dialogue

is false to life, cut to a purely mechanized formula. You cannot separate the speech of one character from another and tell who is speaking. They all talk alike.What must have been particularly hurtful was Adams’s line that in the novel

The famous Hemingway dialogue reveals itself as never before in its true natureimplying that previously Hemingway enthusiasts had been taken in. In For Whom The Bell Tolls, Hemingway also extensively employed dialogue, but in as far as some passages are thoroughly banal and read more like a film script, far too much.

This reader got the distinct impression that he had forgotten to write descriptive passages and chose to compensate by relying heavily on dialogue, many passages of which overstay their welcome and become quite dull. In For Whom The Bell Tolls the one-time ‘modernist’ has also taken his leave.

The often bizarrely stilted language notwithstanding — a result of trying to render idiomatic Spanish in English — the novel is deeply conventional. It also employs a great many adverbs, the qualifiers that are all-too-often used as shorthand by lazy writers.

In For Whom The Bell Tolls, Hemingway also seems to have completely forgotten his own advice on writing, especially his condescending instruction to Scott Fitzgerald in the early 1930s when his star was waxing and Scott’s was waning ‘to leave out the irrelevant stuff’.

Sadly, there’s a great deal of ‘the irrelevant stuff’ in the novel. One wonders what Ezra Pound thought of Hemingway’s celebrated prose if by chance he ever got to read the novel.

For Whom The Bell Toll restored Hemingway’s reputation, but he did not publish anything else for the next ten years until Across The River And Into The Trees appeared and was universally deemed a complete stinker.

At the time of writing it Hemingway was convinced it was his best work yet. Biographer Mary Dearborn believes that delusion was because Hemingway was in a distinct manic phase as part of his bi-polar cycle. Once again the ‘great’ writer seemed to have lost his crown, only to stage another comeback with his novella The Old Man And The Sea in 1952.

Hemingway did not publish any more work in his lifetime, but the success of that last work, a public as well as — broadly — a critical success, ensured that he ended his active writing career on an up-note. The Old Man And The Sea became a mainstay of high school and college English curricula for many years, though over the past decades the work of other writers have dislodged Hemingway from its place as a set text.

It was certainly a distinct improvement on any fiction or non-fiction Hemingway had written since 1929, although it, too, is certainly not flawless. Like me, some might have a distinct distaste of the story’s cloying sentimentality and Christian symbolism which is not just unsubtle but curiously out context. Reviewing the story in the Virginia Quarterly Review, John Aldridge felt that

the prose [in The Old Man And The Sea] . . . has a fabricated quality, as if it had been shipped into the book by some manufacturer of standardized Hemingway parts.Thirty years later writing in The Atlantic, James Atlas was remorselessly downbeat:

The end of Hemingway’s career was a sad business. The last novels were self-parodies, none more so than The Old Man And The Sea. The internal monologues of Hemingway’s crusty fisherman are unwittingly comical (‘My head is not that clear. But I think the great Dimaggio would be proud of me today’); and the message, that fish are ‘more noble and more able’ than men, is fine if you’re a seventh grader.That, in sum, was Hemingway’s output between 1925 and 1952. And that, in sum, is why I am baffled by his repute and find it impossible to persuade myself that I might be ‘missing something’ and that he is after all ‘a great writer’.

Hemingway’s prominence has perhaps diminished over the past four decades, but for many years after his suicide a great many will have classed him as ‘one of America’s greatest writers’ and it seems many still do. I don’t. However, each to his own.